Have you ever wondered about the large metal book press solidly fastened to the circulation desk in the Children’s Room? I hadn’t given it much thought, myself, long assuming that it was just a helpful fixture in the library. We use it to repair books and it couldn’t be handier.

Working in the Community Archives Room (and relatively obsessed with all things historical in the library), I had read the plaque on the counter and knew that the desk had stood in a long-operating, family-owned insurance office here in Gardiner for many, many years. Somehow, however, I never paused to consider just why an insurance office would need a book press….

In the 1830s, Smith Maxcy brought his growing family to Gardiner from Windsor, Maine, and operated a grist mill on Bridge Street. He was widowed three times in his life, raising five sons and three daughters in Gardiner. The eldest son, Josiah, married Eliza Jane Crane and remained in Gardiner, where they raised five sons of their own. In 1853, Josiah established his own insurance agency, which, as several of his sons joined the business, ultimately became Josiah Maxcy & Sons Insurance. It operated for over a century in the upper floors of where Ampersand Dance Studio is now located.

We were lucky to receive a donation of a large collection of Maxcy business and family materials in the Archives some years ago. Josiah and his son William Everett Maxcy were significantly involved in Gardiner business, as well as many municipal and charitable activities and the collection provides amazing glimpses into our local history over many decades.

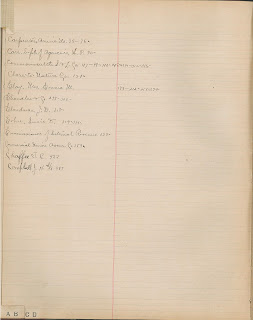

One item, in particular, has fascinated me for some time. It is a book of numbered pages of the thinnest paper – it resembles onion or tracing paper, but even thinner. There is an index in the front of the volume and each of the tissue-thin pages bears a hand-written (or, occasionally, a type-written) letter. All are dated about 1913. When a researching descendent stopped by some months ago, we were equally flummoxed by just what this book was and how it was created. The pages were too thin to write on directly – they would tear too easily – and, clearly, the book contained “copies” of official correspondence sent out by the office. These weren’t carbon sheets and they hadn’t been compiled and bound together after they were created.

Naturally, a Google search helped to deliver some additional evidence and we found both an answer AND a second mystery revealed and solved. It turns out that this bound volume was a “letter book” or a “pressed letter book” and was a state-of-the-art method of copying outgoing correspondence in the mid- to late-19th century and early 20th century.

Much faster than re-writing a copy of a letter, these books required the use of a special copying ink in writing the initial letter and then quickly placing the letter beneath a moistened page of tissue paper in the letter book. Then, with sheets of oil cloth inserted to protect the other pages, the volume was slid into the press and the top was screwed down to tighten and impress the moist page against the freshly written letter. What resulted was an inverse image of the letter on the back of a page of tissue paper thin enough to read properly from the front!

The process may not have required an advanced skill set to complete, but it did demand a bit of savvy in its operation. The sloppy example below was found in our letter book and was likely an instance of too much moisture allowing the ink to bleed.

The explanation of this common technique of copying office papers was simultaneously informative and enlightening. A-ha! Our book press in the Children’s Room had certainly come with the desk when it was donated and it’s long history had absolutely nothing to do with book repair.

Instead, it was likely one of the first and most used “copy machines” in town!